UMA is a decentralized oracle designed to record any type of data on the blockchain, except those that can't be verified.

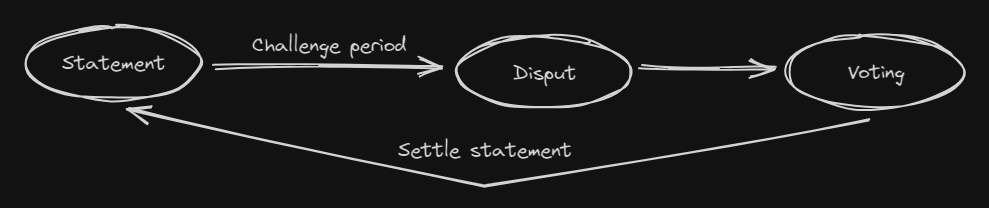

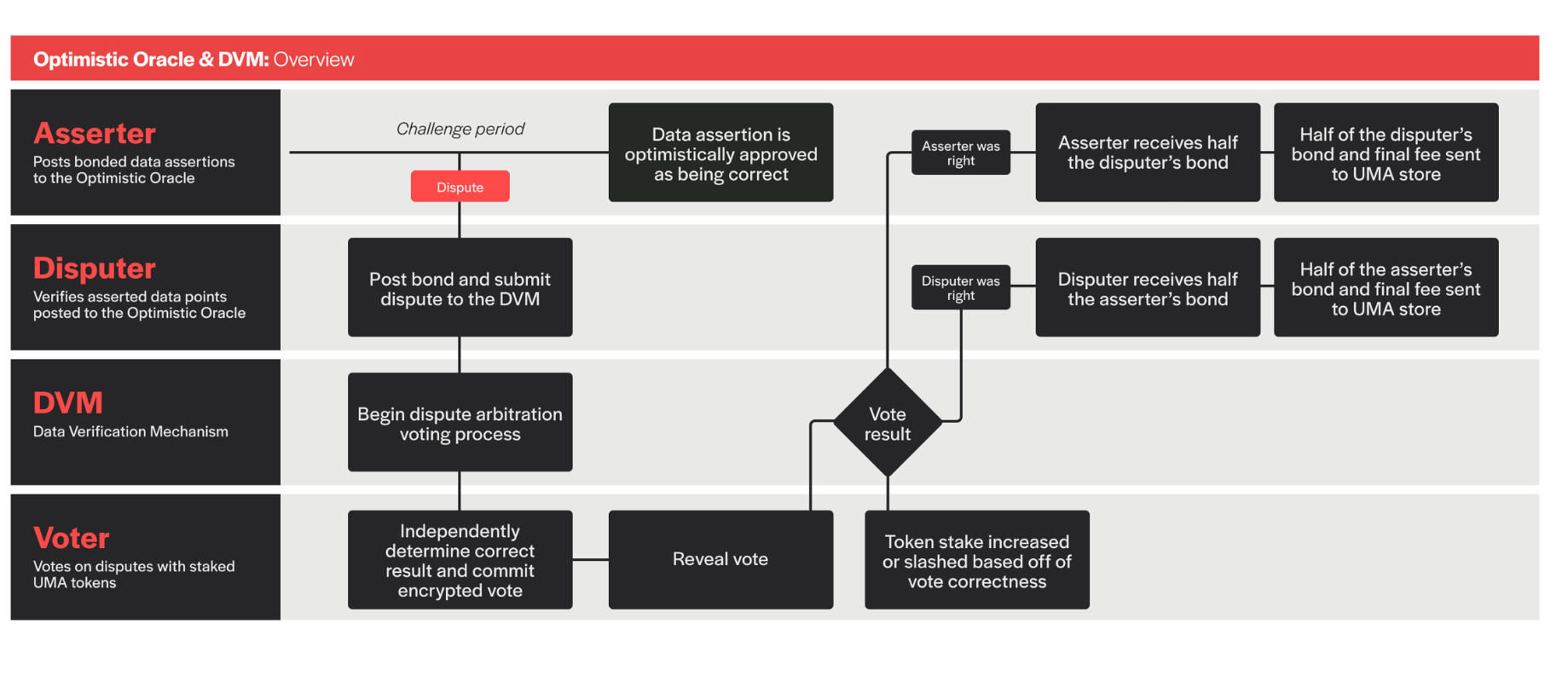

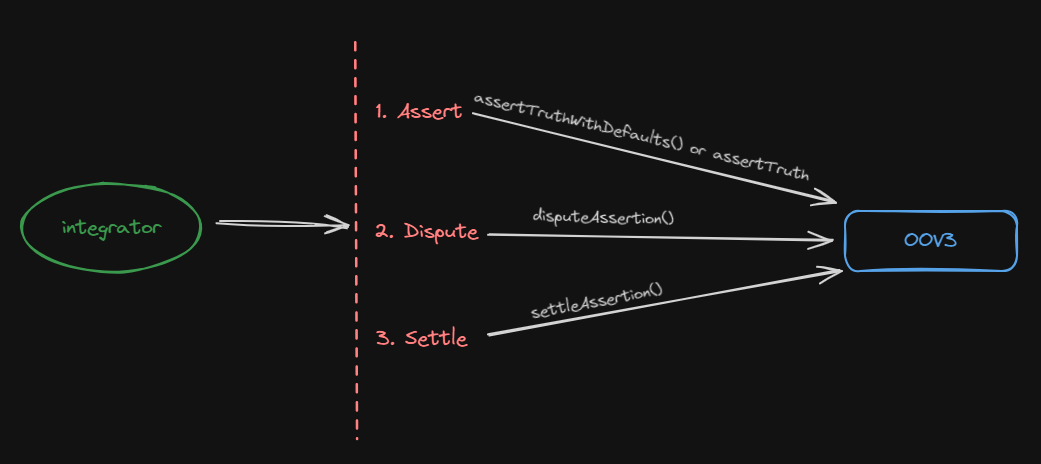

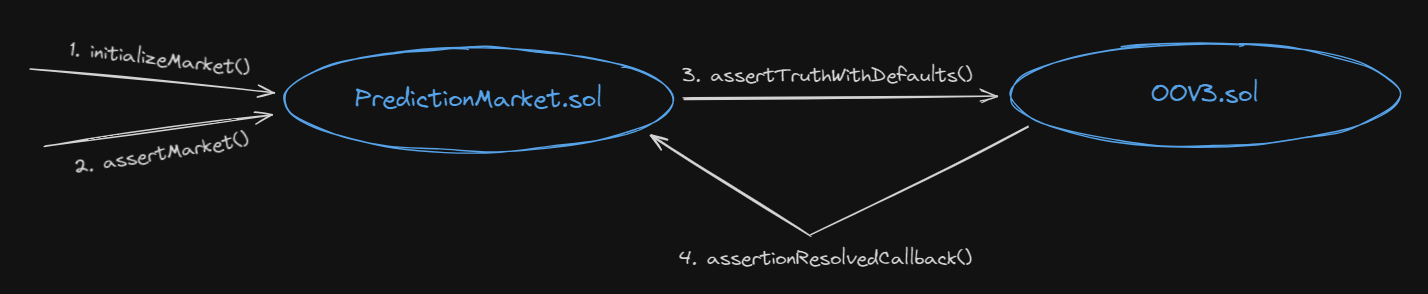

It's called an optimistic oracle because it operates on the assumption that if no one disputes the data, then it's considered accurate. UMA also has a built-in arbitration system to handle disputes.

This oracle provides data for projects like cross-chain bridges, insurance protocols, prediction markets, and derivatives.

The types of data can vary widely — from cryptocurrency prices to sports or political events. However, all the data relates to real-world events that can be verified at some point.

Here are a few examples of such data:

- Elon Musk will tweet about cryptocurrencies before August 31st.

- Trump will say the word «tampon» in an interview.

- There will be a monkeypox outbreak in 2024.

- The price of Solana will be over $140 on August 23rd.

- Satoshi’s identity will be revealed in 2024.